![[Game Warden Archives]](photo/logo2.gif)

By Douglas M. Collister

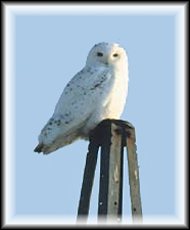

A dark silhouette looking out of place on the power pole several hundred meters ahead catches my attention as I slowly drive a secondary road east of Calgary. It's mid-January and wintering snowy owls should be firmly established on territories by now. I approach as closely as I dare and then pull well over onto the shoulder to inspect the anomalous shape. Through my binoculars I confirm it is an owl although its back is to me and in the dim dawn light I can't rule out a resident great horned owl hunting for a final snack before going to its day roost. The bird has extensive dark markings but the characteristic ear tufts of a great horned are not apparent. Perhaps hearing me, the owl suddenly swivels its head 180 degrees. Piercing yellow eyes set in a white face framed by dark feathers confirms the identification. My first snowy owl of the year, a juvenile female. A dark silhouette looking out of place on the power pole several hundred meters ahead catches my attention as I slowly drive a secondary road east of Calgary. It's mid-January and wintering snowy owls should be firmly established on territories by now. I approach as closely as I dare and then pull well over onto the shoulder to inspect the anomalous shape. Through my binoculars I confirm it is an owl although its back is to me and in the dim dawn light I can't rule out a resident great horned owl hunting for a final snack before going to its day roost. The bird has extensive dark markings but the characteristic ear tufts of a great horned are not apparent. Perhaps hearing me, the owl suddenly swivels its head 180 degrees. Piercing yellow eyes set in a white face framed by dark feathers confirms the identification. My first snowy owl of the year, a juvenile female.

Some snowy owls remain all winter in their far northern breeding range. Otherwise the species is an unpredictable migrant to southern latitudes. Research seems to indicate that the appearance of concentrations of snowy owls in southern Canada correlate roughly with food shortage in the Arctic. However it is unclear whether the heaviest southward movements are composed primarily of young birds produced during a particularly successful breeding effort or of a broad range of age classes which move south due to a general collapse of food resources on the breeding grounds. Supporting the former case was the occurrence in winter 1992/93 of large numbers of emaciated young-of-the-year snowy owls in the Winnipeg area. Supporting the latter were starving birds of all age classes in the Edmonton area during the winters of 1993/94 and 1995/96. Some snowy owls remain all winter in their far northern breeding range. Otherwise the species is an unpredictable migrant to southern latitudes. Research seems to indicate that the appearance of concentrations of snowy owls in southern Canada correlate roughly with food shortage in the Arctic. However it is unclear whether the heaviest southward movements are composed primarily of young birds produced during a particularly successful breeding effort or of a broad range of age classes which move south due to a general collapse of food resources on the breeding grounds. Supporting the former case was the occurrence in winter 1992/93 of large numbers of emaciated young-of-the-year snowy owls in the Winnipeg area. Supporting the latter were starving birds of all age classes in the Edmonton area during the winters of 1993/94 and 1995/96.

Some snowy owls arrive in Alberta from Arctic breeding grounds as early as the beginning of October but most arrive in November and December. Snowy owls that winter in southern Alberta have been found to defend territories. This tendency is most apparent in females with males being more nomadic. Banded birds have been found to return to previous wintering areas which indicates some regularity in seasonal movement between breeding and wintering grounds. Most snowy owls have left the province by the end of March with an occasional bird lingering until the beginning of May. Some snowy owls arrive in Alberta from Arctic breeding grounds as early as the beginning of October but most arrive in November and December. Snowy owls that winter in southern Alberta have been found to defend territories. This tendency is most apparent in females with males being more nomadic. Banded birds have been found to return to previous wintering areas which indicates some regularity in seasonal movement between breeding and wintering grounds. Most snowy owls have left the province by the end of March with an occasional bird lingering until the beginning of May.

Snowy owls breed in open terrain from near the tree line to the edge of polar seas throughout the northern hemisphere. Due to the highly nomadic lifestyle, which presumably results in free genetic flow throughout its holarctic range, no subspecies have been described. Snowy owls breed in open terrain from near the tree line to the edge of polar seas throughout the northern hemisphere. Due to the highly nomadic lifestyle, which presumably results in free genetic flow throughout its holarctic range, no subspecies have been described.

Snowy owls are the largest North American owl, even slightly bigger in overall size than the great horned owl. Although the snowy owl does have ear tufts they are indistinct and rarely noted. Plumage is mostly white and more or less barred and spotted with dusky brown. Females are significantly larger than males. In Alberta a sample of 23 males ranged from 1.6 to 2 kg while 21 females ranged from 1.8 to 3 kg. Adult males are noticeably smaller and paler than adult females. As a rule, the immature owls are the most heavily marked. The darkest males and palest females are virtually alike in color but the whitest birds are always males and the most heavily barred ones are always females. Toes, claws and the short black bill are partly concealed by thick feathers, an adaptation to cold environments. Snowy owls are relatively long-lived with banded birds recaptured up to 17 years later. Snowy owls are the largest North American owl, even slightly bigger in overall size than the great horned owl. Although the snowy owl does have ear tufts they are indistinct and rarely noted. Plumage is mostly white and more or less barred and spotted with dusky brown. Females are significantly larger than males. In Alberta a sample of 23 males ranged from 1.6 to 2 kg while 21 females ranged from 1.8 to 3 kg. Adult males are noticeably smaller and paler than adult females. As a rule, the immature owls are the most heavily marked. The darkest males and palest females are virtually alike in color but the whitest birds are always males and the most heavily barred ones are always females. Toes, claws and the short black bill are partly concealed by thick feathers, an adaptation to cold environments. Snowy owls are relatively long-lived with banded birds recaptured up to 17 years later.

The whitest birds are always males (L) and the most heavily barred ones are always females (R). Photos by D. Collister

During winter snowy owls are more regular and abundant in the northern great plains (including Alberta) than east, west or south of that area. Prime wintering areas closely match the species' tundra breeding habitat. Airports and gently rolling agricultural landscapes are favored with snowy owls selecting specific habitats where prey is most available. Research has shown that age and sex classes are latitudinally stratified on the winter range with immature males wintering farthest south, adult females farthest north and adult males and immature females in between. Winter territories in southern Alberta are primarily held by females and an occasional adult male. During winter snowy owls are more regular and abundant in the northern great plains (including Alberta) than east, west or south of that area. Prime wintering areas closely match the species' tundra breeding habitat. Airports and gently rolling agricultural landscapes are favored with snowy owls selecting specific habitats where prey is most available. Research has shown that age and sex classes are latitudinally stratified on the winter range with immature males wintering farthest south, adult females farthest north and adult males and immature females in between. Winter territories in southern Alberta are primarily held by females and an occasional adult male.

Snowy owls usually perch on the ground or slight rises, sometimes on buildings, telephone poles, fence posts or other prominent structures. Generally sedentary when not flying, they often remain at a commanding perch for long uninterrupted spells. The flight style of snowy owls is distinctive and a good field mark even at a distance. There’s a long deliberate downward sweep followed by a quick and rather jerky upward stroke. They often fly low over the ground and rise sharply to the next perch. Snowy owls usually perch on the ground or slight rises, sometimes on buildings, telephone poles, fence posts or other prominent structures. Generally sedentary when not flying, they often remain at a commanding perch for long uninterrupted spells. The flight style of snowy owls is distinctive and a good field mark even at a distance. There’s a long deliberate downward sweep followed by a quick and rather jerky upward stroke. They often fly low over the ground and rise sharply to the next perch.

Snowy owls are thought to be largely diurnal although some studies have hinted that nocturnal activity may be more extensive than we think. They may hunt in all weather during the winter - even in bright sunshine. In southern Alberta snowy owls frequently "sit-and-wait" while hunting, a technique which studies indicate is successful approximately half the time. They also pursue and capture prey in the air and while standing or walking on the ground. Snowy owls are opportunistic feeders although the main foods in southern Alberta are deer mice and meadow voles. They also prey on ground squirrels, weasels, jackrabbits, a few small birds and gray partridge. Males prey almost exclusively on rodents while females take a wider range of prey. Snowy owls are thought to be largely diurnal although some studies have hinted that nocturnal activity may be more extensive than we think. They may hunt in all weather during the winter - even in bright sunshine. In southern Alberta snowy owls frequently "sit-and-wait" while hunting, a technique which studies indicate is successful approximately half the time. They also pursue and capture prey in the air and while standing or walking on the ground. Snowy owls are opportunistic feeders although the main foods in southern Alberta are deer mice and meadow voles. They also prey on ground squirrels, weasels, jackrabbits, a few small birds and gray partridge. Males prey almost exclusively on rodents while females take a wider range of prey.

Most observers report snowy owls as being very shy and hard to approach closely. Birds usually take flight when an intruder is still 200 to 300 meters away although on occasion an owl will sit boldly on a power pole or other elevated perch while people are active nearby. Most observers report snowy owls as being very shy and hard to approach closely. Birds usually take flight when an intruder is still 200 to 300 meters away although on occasion an owl will sit boldly on a power pole or other elevated perch while people are active nearby.

Many snowy owls that move southward from the Arctic are mistakenly assumed to die from starvation. In Alberta 45 per cent of carcasses examined in one study had moderate to heavy fat deposits. Traumatic injuries were the main cause of death and were sustained through collisions with unknown objects (46.5 per cent), automobiles (14.1 per cent), utility lines (4.2 per cent), and airplanes (1.4 per cent). Other causes of mortality were gunshot wounds (12.7 per cent) and electrocution (5.6 per cent). Only 14.1 per cent of mortality appeared to be due to starvation. Many snowy owls that move southward from the Arctic are mistakenly assumed to die from starvation. In Alberta 45 per cent of carcasses examined in one study had moderate to heavy fat deposits. Traumatic injuries were the main cause of death and were sustained through collisions with unknown objects (46.5 per cent), automobiles (14.1 per cent), utility lines (4.2 per cent), and airplanes (1.4 per cent). Other causes of mortality were gunshot wounds (12.7 per cent) and electrocution (5.6 per cent). Only 14.1 per cent of mortality appeared to be due to starvation.

The snowy owl is the oldest bird recognizable in prehistoric cave art. The outline of a pair of snowy owls and their young was etched into a cave wall in France during a time when the climate rendered much of France suitable as a breeding ground for the species. Humans are the snowy owl's principal predator and have used them for food from at least the last glaciation, based on remains in cave deposits. It is thought that snowy owls are rare in northern Europe due to persecution by man. Presently, with the exception of northern native peoples, it is illegal for anyone to shoot or trap snowy owls for food, sport or trophies. The snowy owl is the oldest bird recognizable in prehistoric cave art. The outline of a pair of snowy owls and their young was etched into a cave wall in France during a time when the climate rendered much of France suitable as a breeding ground for the species. Humans are the snowy owl's principal predator and have used them for food from at least the last glaciation, based on remains in cave deposits. It is thought that snowy owls are rare in northern Europe due to persecution by man. Presently, with the exception of northern native peoples, it is illegal for anyone to shoot or trap snowy owls for food, sport or trophies.

I continue to watch the owl as it patiently scans the surrounding countryside for an unwary vole or covey of partridge. Finally it drops off the pole and flies low and swiftly into the undulating terrain. I follow it as long as I can with my binoculars but inevitably the ghost owl fades into the snowy landscape. I continue to watch the owl as it patiently scans the surrounding countryside for an unwary vole or covey of partridge. Finally it drops off the pole and flies low and swiftly into the undulating terrain. I follow it as long as I can with my binoculars but inevitably the ghost owl fades into the snowy landscape.

|